About

I am an astrophysicist at the Adler Planetarium, working to understand how we can decipher the lives and deaths of stars using phenomena known as gravitational waves.

The Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Illinois.

The Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Illinois.

I grew up in the southwest suburbs of Chicago, and have since jumped around Illinois to study astronomy and physics. I did my undergraduate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with majors in astronomy and physics, with a minor in music performance. Following my undergraduate studies, I took a couple of years off from my studies to pursue music, and during this time also worked as an educator at the Adler Planetarium. I then headed up to Evanston for my graduate studies, and received a PhD in astrononmy and physics from Northwestern University in 2020. Following my graduate studies, I was a NASA Hubble Fellow, Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics Fellow, and Enrico Fermi Fellow at the University of Chicago from 2020-2023.

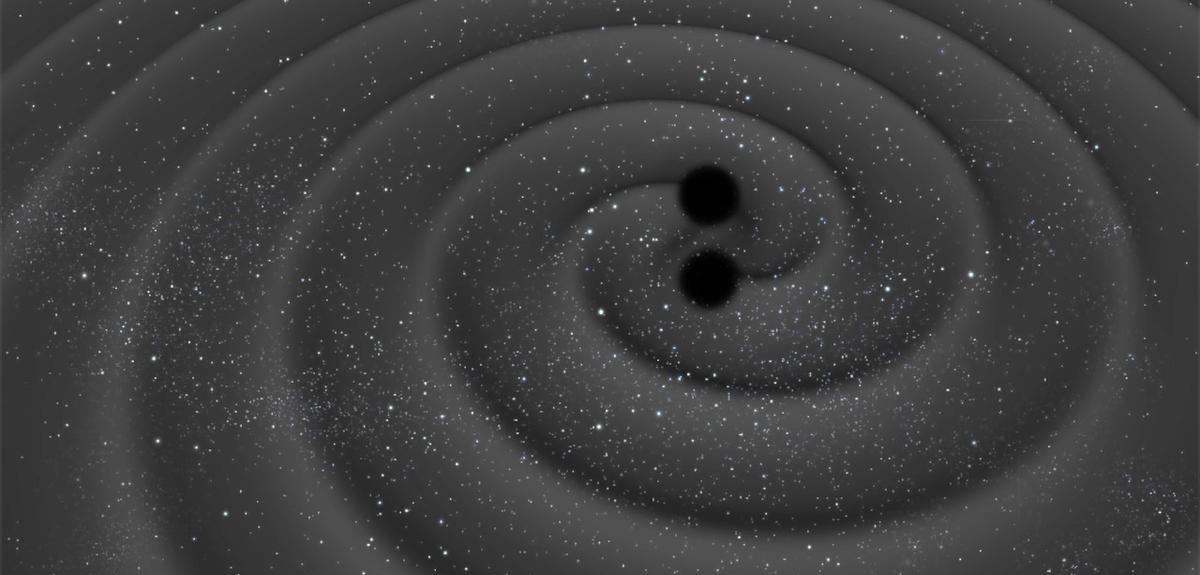

Artist’s impression of two black holes inspiraling and emitting gravitational waves. Credit: C. Carreau/ESA.

Artist’s impression of two black holes inspiraling and emitting gravitational waves. Credit: C. Carreau/ESA.

So what are gravitational waves anyway, and why do astronomers care about them? Predicted by Einstein over a century ago, gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of spacetime. Though any accelerating mass emanates gravitational waves, spacetime is very stiff and only extreme systems in the Universe can generate signals strong enough for us to sense. I am a part of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which made the first observation of these elusive signals in 2015. The culprit: two black holes about a billion lightyears away, each around 30 times more massive than our Sun, spiraling in towards one another and merging.

Since this groundbreaking discovery, we’ve observed dozens more gravitational-wave events, coming from both black holes and neutron stars. These dark objects are the remains of massive stars when they die, and gravitational waves are providing a new means for observing and characterizing them in the Universe. I aim to use the growing population of these observed compact objects to decipher information about their progenitors and better understand the impact that they have on the universe as a whole:

- What type of environments were they born in?

- What processes took place during the lives of their stellar progenitors?

- What can we learn about the supernova explosions that create compact objects?

- How do compact object mergers chemically enrich their environments with the heavy elements forged during their explosive merger?

- What can compact object mergers tell us about star formation across over cosmic time?

- What do the host galaxies of compact object mergers teach us about their massive-star progenitors?

I’m also heavily involved in citizen science, and helped to build a project called Gravity Spy in which volunteers from the general public can help analyze gravitational-wave data.

You can find more about my specific research interests and a full list of my academic publications on this site.

Globular cluster 47 Tucanae imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Deep in the core of globular clusters such as this one, black holes are believed to interact with one another, merge, and emanate gravitational waves. Credit: NASA/ESA.

Globular cluster 47 Tucanae imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Deep in the core of globular clusters such as this one, black holes are believed to interact with one another, merge, and emanate gravitational waves. Credit: NASA/ESA.

Outside of astrophysics research I pass the time playing music: classical piano and string bass as well as bass guitar in a Chicago-based rock band (click here to listen to us on Spotify). I love traveling, hiking, and getting lost in new corners of the world. In the winter you can usually find me snowboarding down a mountain. Tennis is my favorite form of exercise, and I’m a huge board game/video game nerd. I’m also passionate about science education and outreach; you can find more about my public speaking and outreach iniatives on this site.